Wright, Harry, 1835-1895

Inducted to the Hall of Fame in: 1953

Primary team: Philadelphia Phillies

Primary position: Executive

Hall of Famer Henry Chadwick once wrote: “There is no doubt that Harry Wright is the father of professional base ball playing.”

Wright, who was born in England and raised as a cricket player, warrants credit for founding the first all-professional baseball team and serving as a major pioneer for the exponential growth of baseball during the 19th century.

Born Jan. 10, 1835 in Sheffield, England, Wright and his family immigrated to New York City when he was still an infant. His father, Samuel, became a top cricket professional for the St. George Dragonslayers club in Harlem and taught him the rules of the sport. By age 14, Harry had dropped out of school to join his father on the Dragonslayers.

In 1857, St. George moved across the Hudson River to the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, N.J., for more playing space. While there, Wright saw his first baseball games played by the New York Knickerbockers and quickly became interested in the American sport.

Wright joined the Knickerbockers and became the team’s first openly paid player in the early 1860s. He switched to the New York Gothams during the Civil War and then became one of Cincinnati’s best pitchers by 1866. Also a fine cente rfielder, Wright is credited with hitting seven home runs in a game in 1867.

By the end of the decade, Wright’s ambitions had blossomed from simply playing baseball to assembling the game’s premier club. With financial backers behind him, Wright scoured the country to sign the best players he could find – none better than his younger brother, George.

Credited as one of the first coaches in American sport to fully adopt the concept of teamwork, Harry Wright drilled his players during the spring of 1869 to prepare for a tour against East Coast teams.

“Contestants for the championship will have to keep one eye trained toward Porkopolis,” the New York Clipper wrote referring to Wright’s Cincinnati team. However, no one in baseball could have fully anticipated the impending success of the Red Stockings. After rattling off 18 straight wins against weaker competition, Cincinnati traveled east and simply rolled through the nation’s best known baseball teams. Wright’s club began by defeating the highly-regarded New York Mutuals 4-2, then routed the previously unbeaten Brooklyn Atlantics 32-10. Led by George Wright at shortstop, the Red Stockings compiled a perfect 57-0 record in 1869.

“The result of the season’s play places the Cincinnati club ahead of all competition,” wrote the Clipper, “and we hail them as the champion club of the United States.”

The unbeatable Red Stockings became icons of American sport, traveling from Boston to San Francisco and drawing an estimated total attendance of 200,000. But in 1870, other teams began to catch up to Wright’s once indomitable club. Cincinnati lost six games, causing fans to abandon the team. Citing financial pressures, the Red Stockings’ board of directors disbanded the team following the 1870 season and returned it to amateur status.

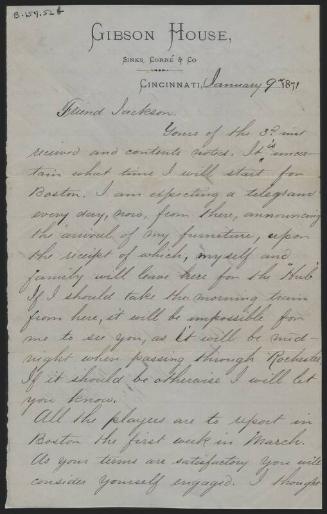

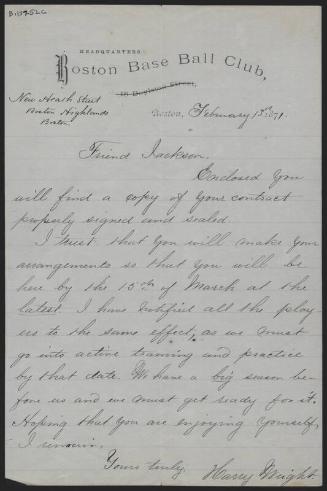

Wright was undeterred by his team’s dissolution and chose to start from scratch. In 1871, he and his brother moved to Boston and created a new Red Stockings team that would compete in the brand new National Association. After a disappointing debut season in which George broke his leg, the new Red Stockings came to dominate the league and claimed four consecutive pennants. In 1875, Harry Wright captained Boston as player-manager to a remarkable 71-8 record.

Wright’s managerial acumen, combined with the Red Stockings’ formidable collection of talent, made the phrase “Break up the Bostons!” a popular rallying cry among National Association opponents. It was Boston’s dominance that partially motivated Hall of Fame executive William Hulbert to create the National League in 1876 and distance his Chicago club from the indomitable Wright brothers.

However, Wright and his Red Stockings would flourish in Hulbert’s new league as well. After a fourth-place finish in 1876, Boston won 69 percent of its games from 1877-78 to claim two National League pennants.

“It is true Mr. Wright is not infallible, and he is apt to err, just as any other person in his particular profession will blunder,” noted one newspaper from the era. “But Mr. Wright will make 49 good (decisions) to every bad one.”

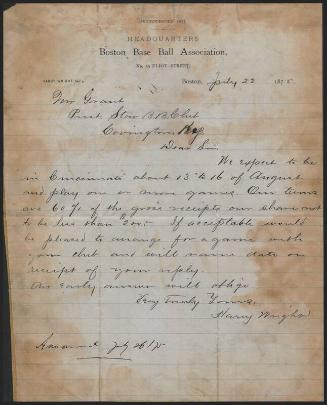

Wright would go on to manage for 15 more seasons with Boston, Providence and Philadelphia. He finished with a then-record 1,225 victories and six total pennants from two different leagues.

“No death among the professional fraternity has occurred which elicited such painful regret,” wrote Chadwick upon Wright’s passing on Oct. 3, 1895. “[Harry Wright was] the most widely known, best respected and most popular of the exponents and representatives of professional baseball, of which he was virtually the founder.”

Wright was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1953.