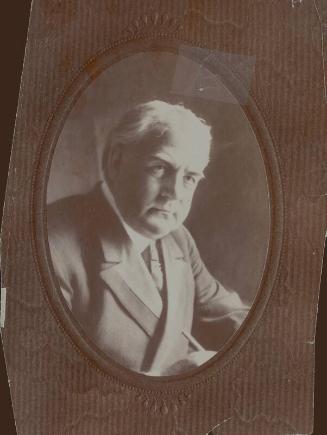

Harridge, Will, 1881-1971

Primary position: Executive

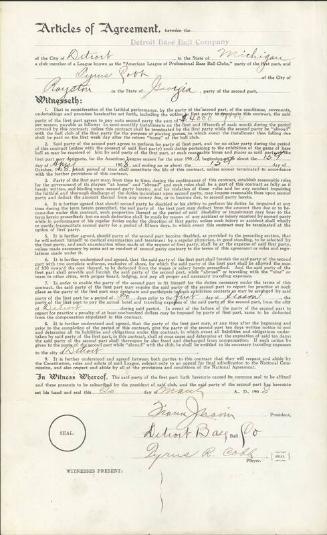

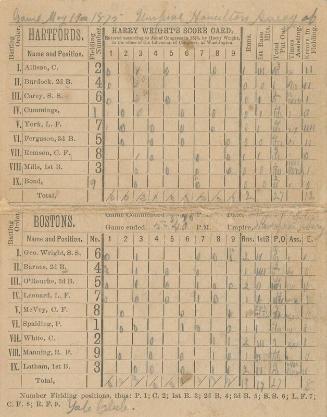

At the turn of the 20th century, Will Harridge worked as a ticket agent for the Wabash Railroad Company and was in charge of booking and transportation for American League teams and umpires.

By 1931, Harridge was directing AL policies as the league’s third president.

“Harridge’s life was like something straight out of Horatio Alger,” wrote the Sporting News upon his death. “He was a poor boy who climbed to the top through diligence, courage and integrity. In his case, the story wasn’t fiction.”

In December 1911, Harridge received his break when AL President Ban Johnson hired him as his personal secretary and doubled his salary. While Johnson was impressed with Harridge’s work at Wabash, the hiring was still remarkable in the fact that Harridge claimed to have never played a baseball game.

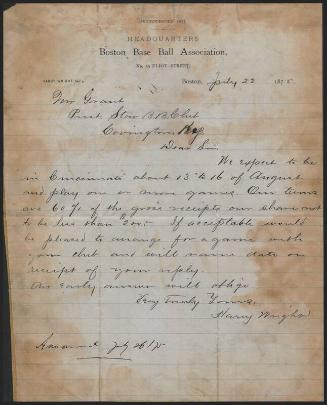

Johnson was looking for a man who could run his office and manage his correspondence, and Harridge proved adept at those tasks. He dutifully held the role of Johnson’s secretary until Johnson’s resignation in 1927, when he was promoted to secretary of Major League Baseball under commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis.

Harridge continued to work under new AL President Ernest Barnard until Barnard’s death in 1931.

“I nominate Will Harridge for president and treasurer,” St. Louis Browns owner Phil Ball at a special league meeting that year. “I hope he is not elected, for, if he is, we are going to lose a darn good secretary.”

The AL owners initially hired Harridge to a three-year term as interim president, but Harridge would hold the title for the next 27 years. His tenure was known more for its quiet diligence as opposed to the boisterous years of Johnson. Harridge reportedly did not take an extended vacation for his first 19 years in office.

“There was never a morning when I didn’t look forward to going to my office,” Harridge said.

His biggest test came in his second year in office, when New York Yankees catcher Bill Dickey reacted to a hard slide by the Washington Senators’ Carl Reynolds and delivered a punch that broke Reynolds’ jaw. Despite Dickey’s standing as a star of the league’s most successful franchise, Harridge fined Dickey $1,000 and suspended him for 30 days.

“[Yankees owner] Col. Jake Ruppert was furious,” Harridge later recalled. “He didn’t talk to me for almost a year. But the following winter he was elected vice president, and he gradually softened up and became one of my best friends.”

In 1933, Harridge made arguably his biggest contribution to baseball by helping to create the All-Star Game. Inspired to the idea by Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward, Harridge lobbied AL owners to approve the inaugural interleague contest at Comiskey Park. The game, originally scheduled to be a one-time event, was such an overwhelming success that it became an annual tradition.

Harridge’s pride in his league was so strong that the Sporting News wrote that Harridge “wanted to win every All-Star Game just as much as he did the World Series.” In the summer of 1941, after Hall of Famer Ted Williams won the Midsummer Classic for the AL with a game-winning home run, Harridge hugged Williams and later admitted: “I’d have kissed him, if there had not been so many people around.”

Harridge saw his league expand to new markets in the 1950s as the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore and the Philadelphia Athletics relocated to Kansas City. He retired from the president’s office in 1958 but remained as Chairman of the Board for the AL until his death in 1971.

Harridge passed away on April 9, 1971. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1972.